Following on from my last post, here are some more links to some interesting online content that is related to the topics I write about here, along with some commentary from me. First of all, have a look once again at the blogroll in the sidebar -- I've added some more blogs, including Whats in a brain? which has a recent post on linguistic relativity and time. Now in today's post I've got some longer lecture-type items, mostly by academics but aimed at a broad non-specialist audience. Wherever possible I'll try to include links to both video and audio versions for you to choose from.

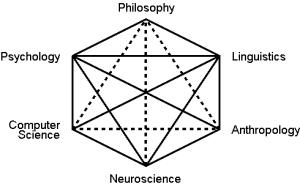

First of all is a talk by James Burke titled "Admiral Shovel and the Toilet Roll" (also available in iTunes). In addition to his usual connections approach, this is an excellent argument for the importance of the interdisciplinary approach. It's also very witty and entertaining, as usual for Burke.

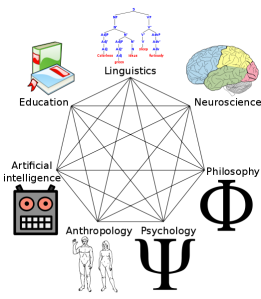

At the end of the last post I linked to some basic introductory linguistics videos, and here is another very good introduction to the basics of linguistics, "Linguistics as a Window to Understanding the Brain" by Steven Pinker. This lecture is part of the Floating University initiative, and in it Pinker does a pretty good job of not only presenting basic linguistic concepts but also introducing and giving a balanced treatment of some controversial issues such as language universals and linguistic relativity, subjects that he has fairly strong views on. Here is the lecture on YouTube:

Related to the subject of language universals is Daniel Everett's Long Now lecture "Endangered languages, lost knowledge and the future" (the audio is also available in iTunes and the video can be watched on Fora.tv). Based on his observations of the Pirahã language, Everett argues against the Chomskyan notion of an innate universal grammar, and instead suggests that language is a cultural tool invented by humans to serve a social function.

Lera Boroditsky gives an excellent introduction to recent research on the subject of linguistic relativity in her Long Now lecture "How Language Shapes Thought" (the audio is also available in iTunes and the video can be watched on Fora.tv). In particular, Boroditsky many of the language and time issues I've written about recently. Here is the lecture on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPGpZp1pfQQ&w=560&h=315

On the subject of time, here is Claudia Hammond's RSA talk "Time Warped" based on her book of the same name (the full audio of the talk is also available in iTunes). Hammond discusses many interesting issues about time perception. Here is a YouTube video of the edited highlights of this talk:

Cognitive scientist David Eagleman also works on time perception (as well as a variety of other topics). Here are two lectures of his from The Up Experience. In the first, he gives good summary of his work on how we perceive time and how our sense of time is largely a construction by the brain:

In this second Eagleman talk, he discusses, among other things, the relationship between the present self and the future self, drawing on a story of Odysseus and the sirens from the ancient Greek epic The Odyssey to describe what he calls the Odysseus contract:

Economist M. Keith Chen also draws on the idea of future discounting, which Eagleman refers to in that last video, in his highly controversial connection between how languages handle the future tense and future planning (which I've discussed before here and here). Here is his TED talk presenting this theory:

Psychologist Philip Zimbardo talks about our orientation to time, that is being past, present, or future oriented, and what this means to the way we approach life, also touching large scale cultural differences, in his RSA talk "The Secret Powers of Time". Here are the YouTube videos of both the full lecture and the excellent 10-minute RSA Animate video excerpted from it:

And finally, since I started this post with James Burke's kind of connections, I'll end with neuroscientist Sebastian Seung's TED talk "I am my connectome", in which he discusses his connectome project of mapping the brain's neuronal connections, and related book Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are:

I'll hopefully be able to get back to more substantive blogging later on in August, but for now good watching/listening!