I wanted to write today about something that is in many ways central to much of what I write about here on this blog, and has been fundamental to much of my research more generally: interdisciplinarity. For those not that familiar with academia, universities are generally rigidly divided into a variety of disciplines. At the larger level, there are main groupings such as the sciences and humanities, which are further divided into departments such as physics, biology, English literature, history, and philosophy. There are certainly good organizational reasons for this kind of division, as it fosters in depth interaction within disciplines with others working on similar areas, and puts researchers and students with others of a like mind, who might best be able to appreciate their shared material.

I suppose ultimately this kind of division goes back to the medieval arrangement of education into what is known as the trivium and the quadrivium. The first level, the trivium with three subjects, is what we might now think of as the arts: grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic (that is logic). The second level, the quadrivium with four subjects, consisted of what we might call the sciences: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music (that is the theoretical study of harmonics). The word trivium means literally ‘three ways’ (referring obviously to the three parts) from Latin tri- ‘three’ and via ‘way, road’, and on a more literal level the same word was used to refer to a crossroad of three streets. From this also comes the modern English word trivial.1 Now I’m not suggesting that intense specialisation is trivial,2 but the research produced from increasingly specialised disciplines runs the risk of being appreciated by only a small few who are in the know. Now this kind of detailed work is very important at advancing and solidifying what we know about the world -- quantum physicists may discover the fundamental operations of reality or paleographers may determine the provenance of a particular manuscript. But sometimes great advances come from the unexpected intersection of different knowledge sets, and because few people can be experts in more than one field, these kinds of perspectives can be missed.

This serendipity is at the heart of much of the writing of the popular science historian James Burke, and indeed Burke makes a particularly strong case for this kind of boundary crossing in this podcast, if you care to listen. The point is, groundbreaking discoveries often come from people working outside of their normal, comfortable, well-defined area of study, exploring areas outside their comfort zone. Sometimes they connect the familiar with the unfamiliar. Or they connect an external idea with their usual subject matter. This is in part what lies behind interdisciplinarity.

My background, as I've mentioned before, is in medieval studies, which combines a variety of disciplines such as language, literature, palaeography, codicology, history, archaeology, musicology, and so forth, over a wide geographical range, with the unifying chronological parameter of the middle ages. My doctoral dissertation would not have been possible in an English literature department, combining as it did linguistics, literature, anthropology, philosophy, history, and a variety of other approaches. It may have left me as something of a jack of all trades, master of none, but it allowed me a range that I found quite interesting. Cognitive science, my latest interest, is also an example of an interdisciplinary field, even more so when applied to literature, culture, or history, as researchers like myself do.

Recently I've noticed some quite inventive interdisciplinary projects worthy of note. Culturomics, applying detailed quantitative analysis to a large database of texts with a view to making cultural connections, has garnered some broad attention, particularly with a recent paper examining the birth and death of words. This culturomics approach has led to the Google ngram tool, which is free for anyone to play around with. Searchable electronic corpora of texts are often only available to those within an academic institution, and take some specialised knowledge to use. When I work with Old English, for instance, I make extensive use of the Old English Corpus from the Dictionary of Old English Project. The ngram tool from Google allows anyone to experiment.

Closer to my own background in Old English, there is the Lexomics project, which bring statistical analysis and computer science to the study of Old English poetry. This project has taken the Old English Corpus and applied some quite sophisticated statistical analysis with a view to finding lexical connections between different texts. This could, for instance, be used for research on authorship or literary influence. And again, many of the Lexomics tools are freely available online.

And as I've written about before, M. Keith Chen has tried to explore the intersection of economics, language, and psychology, and Chen’s other work also employs similar cross-boundary approaches, as is clear from his website.

Of course, inevitably such boundary pushing research will be criticised by specialists in the fields, sometimes rightly and sometimes not. Naturally when working outside of your comfort zone you may make faulty assumptions that a specialist would not, and thus the scrutiny of specialists is important for refining this kind of work. I’ve already written about the criticisms of Chen’s linguistic relativistic effects on saving behaviour. There are, indeed, some potentially serious problems to his categorisation of languages, and perhaps with the type of statistical analysis he uses. Nevertheless, I think this research raises some interesting questions, which merit further investigation. While I don’t think Chen has definitively proven anything, I do think that he has cast a light on an intriguing correlation between language and thought, which can be further explored with both statistical and experimental work. And the Culturomics work has similarly been criticised due to problems with the corpus of texts they’re working with.3

In particular, I’m personally quite fascinated by scientific approaches to literature and the humanities in general, bridging that traditional trivium/quadrivium divide I mentioned earlier. Culturomics is one such example, conducted as it is by physicists and mathematicians. Another science/humanities crossover is the project to determine the provenance of medieval manuscripts by analysing the DNA of the parchment. My own post on the history of sailing technology in its way is a cross over between science and the humanities. And one thing the sciences do well, that is often not a factor in the humanities, is collaboration. I’d like to see more collaborative work in the humanities.

So in the end, all of this was to call attention to the basis of much of what I’m writing about on this blog. As I’ve said, my research, including my doctoral dissertation, is inherently interdisciplinary. I use language as an entry point to investigate history, culture (including literature), and thought. On this blog I may push the boundaries even further than I do in my other research in an effort to see what sticks. I do think that by taking those chances real progress can be made, but I certainly do welcome any constructive criticism.

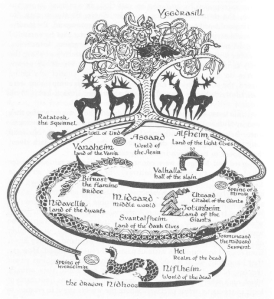

Coming up soon, a related post on interconnectedness...

![The Oksapmin counting system. The conventional sequence of body parts used by the Oksapmin. In order of occurrence: (1) tip^na [thumb], (2) tipnarip [index finger], (3) bum rip [middle finger], (4) h^tdip [ring finger], (5) h^th^ta [pinky], (6) dopa [wrist], (7) besa [forearm], (8) kir [elbow], (9) tow^t [biceps], (10) kata [shoulder], (11) gwer [neck], (12) nata [ear], (13) kina [eye], (14) aruma [nose], (15) tan-kina [eye on other side], (16) tan-nata [ear on other side], (17) tan-gwer [neck on other side], (18) tan-kata [shoulder on other side], (19) tan-tow^t [biceps on other side], (20) tan-kir [elbow on other side], (21) tan-besa [forearm on other side], (22) tan-dopa [wrist on other side], (23) tan-tip^na [thumb on other side], (24) tan-tipnarip [index finger on other side], (25) tan-bum rip [middle finger on other side], (26) tan-h^tdip [ring finger on other side], (27) tan-h^th^ta.s [pinky on other side]. The Oksapmin counting system](http://endlessround.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/oksapmin01.gif)