As a bit of a departure, this week’s video isn’t about the etymology of a single word, but about a person who had an important impact on both science and language, Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles:

The idea of doing a person-centred video rather than using a word as a jumping off point was suggested to me by Theo Rodriguês in his response to my request for feedback over the summer, and the result is something of an epic, at nearly 20 minutes my longest video yet. Erasmus Darwin was the first candidate to come to mind for this project, since even though I mentioned him already (in “Coach”, “Clue”, and “Gimlet”), there was still so much more to say about him. Darwin is interesting not only for his wide-ranging scientific interests, but also for his word coining and literary efforts. He is the 770th most quoted source in the Oxford English Dictionary, and that ranking includes multi-author sources such as the Bible and the Times. Darwin provides 68 instances of the first known evidence for a new word (ranking him as 511th in the OED), and a further 204 earliest citations for new senses of existing words (thus coming in at a ranking of 548). Not bad for a person not principally known for his body of literature. There is one article in particular that I’m indebted to for this video, Desmond King-Hele’s “Erasmus Darwin, Man of Ideas and Inventor of Words” (see show notes for source info). Darwin began his literary career early on with a published poem about the Prince of Wales, but mainly he is known for scientific writings, including what I find most interesting about him, poetry about science. This is a perfect example of the interdisciplinary ideal, and his stated intention to “enlist imagination under the banner of science” is the perfect motto for the recent boom in science communication (about which more below). The other major inspiration for this video was seeing rapper Baba Brinkman perform his Rap Guide to Evolution a year ago. I noticed a real parallel between what Baba was doing and what Darwin was trying to accomplish in his day, popularizing and teaching science through poetry. Indeed for a while Darwin was quite successful, with his writings becoming the science “bible” for literary types, especially the Romantics. Makes sense, since they were really into the natural world Darwin was describing, and he did so in such reverential and downright spiritual terms. Exactly the sort of thing the Romantics loved. (See my video “Sublime” for more on the Romantics). Like the Romantics too, Darwin was also something of a social activist and revolutionary. He was a staunch abolitionist, and wanted to set up a dispensary for the poor. He also strongly supported religious toleration and freedom of the press. And finally, Darwin is also an excellent example of the interconnected world, with many social connections and people he helped or inspired. I only touched on a small number of the possible connections in the video (and in this blog), but this concept map image from my database (created with TheBrain software) gives something of an idea of the complexity involved.

Taking a closer look at Darwin’s scientific investigations, he was well connected in the scientific community, for instance keeping up a correspondence with geologist James Hutton, whose contributions to evolutionary science I touched on in the “Fossil” video. Actually, Darwin’s connection to evidence for evolution stretches back to his own father, who found the first known specimen of a fossilized plesiosaur, not that they knew what it was at the time. Darwin’s own speculations about evolution go beyond just the origins of life; his great poem The Temple of Nature also describes the evolution of civilization, including the development of language:

"From these dumb gestures first the exchange began

Of viewless thought in bird, and beast, and man;

And still the stage by mimic art displays

Historic pantomime in modern days;

And hence the enthusiast orator affords

Force to the feebler eloquence of words.

"Thus the first Language, when we frown'd or smiled,

Rose from the cradle, Imitation's child;

Next to each thought associate sound accords,

And forms the dulcet symphony of words;

The tongue, the lips articulate; the throat

With soft vibration modulates the note;

Love, pity, war, the shout, the song, the prayer

Form quick concussions of elastic air.

"Hence the first accents bear in airy rings

The vocal symbols of ideal things,

Name each nice change appulsive powers supply

To the quick sense of touch, or ear or eye.

Or in fine traits abstracted forms suggest

Of Beauty, Wisdom, Number, Motion, Rest;

Or, as within reflex ideas move,

Trace the light steps of Reason, Rage, or Love.

The next new sounds adjunctive thoughts recite,

As hard, odorous, tuneful, sweet, or white.

The next the fleeting images select

Of action, suffering, causes and effect;

Or mark existence, with the march sublime

O'er earth and ocean of recording Time.

According to his idea then, language developed gradually out of gesture and expression, eventually developing the ability to express more and more abstract ideas. Darwin always included copious explanatory notes with his poetry, so as he goes on to explain about this passage:

“There are two ways by which we become acquainted with the passions of others: first, by having observed the effects of them, as of fear or anger, on our own bodies, we know at sight when others are under the influence of these affections. So children long before they can speak, or understand the language of their parents, may be frightened by an angry countenance, or soothed by smiles and blandishments. Secondly, when we put ourselves into the attitude that any passion naturally occasions, we soon in some degree acquire that passion; hence when those that scold indulge themselves in loud oaths and violent actions of the arms, they increase their anger by the mode of expressing themselves; and, on the contrary, the counterfeited smile of pleasure in disagreeable company soon brings along with it a portion of the reality, as is well illustrated by Mr. Burke. (Essay on the Sublime and Beautiful.) These are natural signs by which we understand each other, and on this slender basis is built all human language. For without some natural signs no artificial ones could have been invented or understood, as is very ingeniously observed by Dr. Reid. (Inquiry into the Human Mind.)”

Some other passages worth quoting here include the full description of the Big Bang and Big Crunch, which I abbreviated in the video, as it is such a wonderful bit of poetry:

Roll on, ye Stars! exult in youthful prime,

Mark with bright curves the printless steps of Time;

Near and more near your beamy cars approach,

And lessening orbs on lessening orbs encroach; —

Flowers of the sky! ye too to age must yield,

Frail as your silken sisters of the field!

Star after star from Heaven's high arch shall rush,

Suns sink on suns, and systems systems crush,

Headlong, extinct, to one dark center fall,

And Death and Night and Chaos mingle all!

— Till o'er the wreck, emerging from the storm,

Immortal Nature lifts her changeful form,

Mounts from her funeral pyre on wings of flame,

And soars and shines, another and the same.

I also referred to a “pasta” experiment that may have been the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Here’s the experiment in question, described in the notes to The Temple of Nature: “in paste composed of flour and water, which has been suffered to become acescent, the animalcules called eels, vibrio anguillula, are seen in great abundance; their motions are rapid and strong … even the organic particles of dead animals may, when exposed to a due degree of warmth and moisture, regain some degree of vitality”. In addition to life sciences, Darwin also made important contributions to meteorology, explaining cloud formation, weather fronts, and suggesting the utility of weather maps, and invented weather measuring instruments, and as I mentioned in the video, he coined such terms as anemology and devaporate.

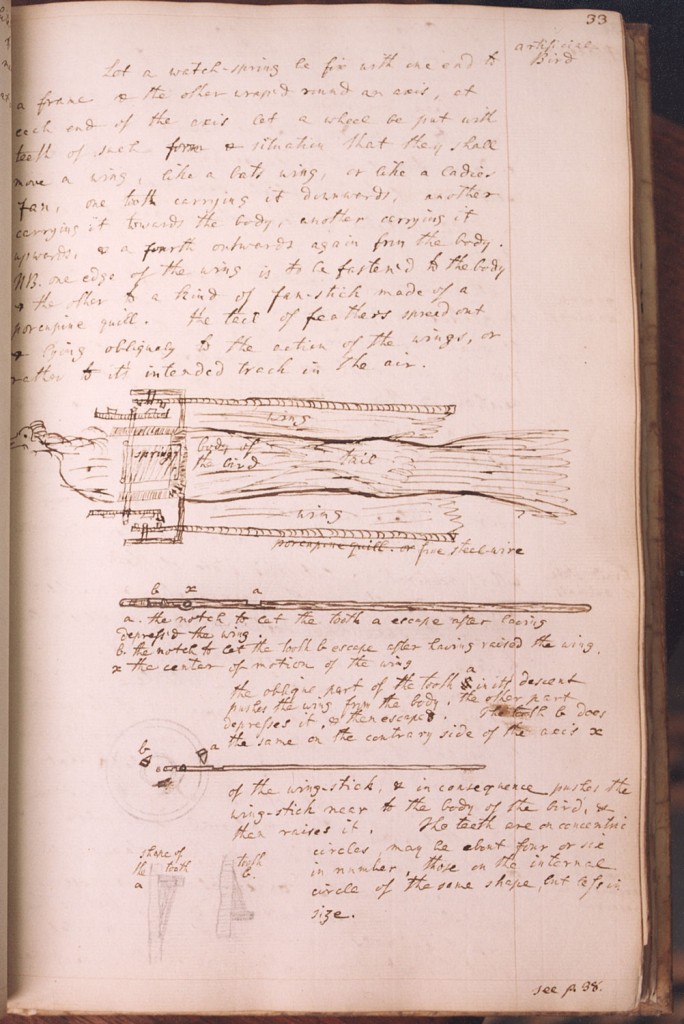

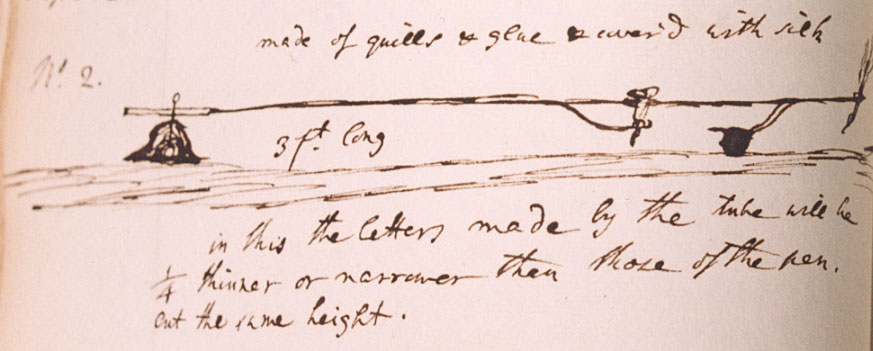

Darwin attempted yet another replication of the natural world in his creation of a mechanical bird, an important milestone in both the fields of aviation and animatronics, as we now call it—though Darwin didn’t invent that word, it was Walt Disney. Here’s Darwin’s sketches of his mechanical bird and an earlier sketch of a copying machine, the bigrapher, before he went on to develop the polygrapher which he handed over to Greville to no avail, as mentioned in the video:

Darwin was a great supporter of the work on steam power of Watt and Boulton, and even came up with his own design for a steam-powered car in 1763, which he offered to Boulton to develop, but alas Boulton like Greville never developed it, and six years later Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot build the first steam-powered automobile. Darwin did, however, manage to put into practise numerous improvements to the carriage, important to him since he spent much of his time travelling the countryside making house calls on his patients. He made his carriage more stable, with a smoother ride, and devised a novel steering system still used in cars today, though known as Ackermann steering, since Darwin didn’t want to patent the idea himself, and it was “reinvented” by Georg Lankensperger and subsequently patented in England by his agent Rudolph Ackermann. But perhaps spare a thought for Erasmus Darwin next time you’re behind the wheel of a car.

In the video I mention his crest and motto “e conchis omnia” (‘everything from shells’); here’s the original crest:

You can see the three shells on the diagonal banner in the middle. For Darwin, the shell becomes a symbol of the creation of life and by extension the famous imagery of Venus on the shell in Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus”, especially in light of the idea of the creation of life:

Witness this passage from The Temple of Nature:

Rose young Dione from the shoreless main;

Type of organic Nature! source of bliss!

Emerging Beauty from the vast abyss!

Sublime on Chaos borne, the Goddess stood,

And smiled enchantment on the troubled flood;

The warring elements to peace restored,

And young Reflection wondered and adored."

Now paused the Nymph,—The Muse responsive cries,

Sweet admiration sparkling in her eyes,

"Drawn by your pencil, by your hand unfurl'd,

Bright shines the tablet of the dawning world;

Amazed the Sea's prolific depths I view,

And Venus rising from the waves in You!

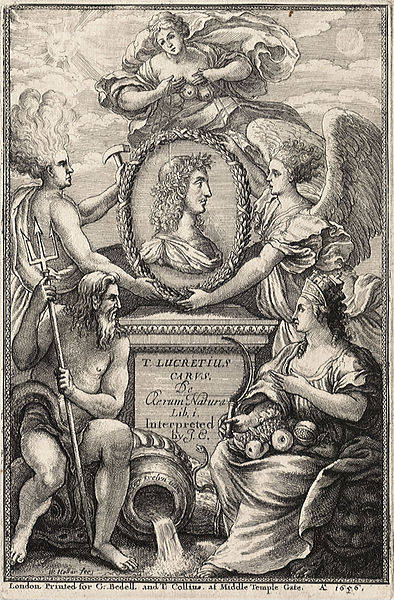

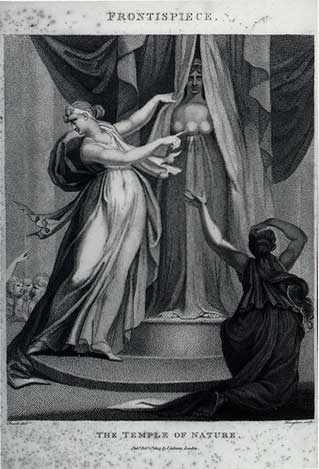

Furthermore, there might be a Venus reference in the frontispiece to The Temple of Nature. De Rerum Natura by Lucretius, a major inspiration for Darwin’s creation poem, opens with an invocation to Venus as a symbol of creation, and if you compare the frontispiece of the translation of Lucretius written by John Evelyn you can spot an interesting parallel:

The curious thing is in both cases the “Venus” figure is pictured with many breasts, a motif now associated with a cult image of Artemis at the temple of Ephesus (though there’s now some dispute about whether they’re breasts or something else on the statue). Here’s an image of the Artemis of Ephesus, similar to Egyptian artistic style, that would have been known at the time:

I’d be very interested in hearing from anyone who might know what’s going on here with the many breasts motif. The figure must be meant to represent Venus, so perhaps the many breasted Artemis figure was thought at the time to be Venus? Also, is the one frontispiece a direct reference to the other, or is this a common motif? It’s curious to say the least. It’s especially intriguing in light of Darwin’s explanatory note about the Venus passage in his poem:

The hieroglyphic figure of Venus rising from the sea supported on a shell by two tritons, as well as that of Hercules armed with a club, appear to be remains of the most remote antiquity. As the former is devoid of grace, and of the pictorial art of design, as one half of the group exactly resembles the other; and as that of Hercules is armed with a club, which was the first weapon. The Venus seems to have represented the beauty of organic Nature rising from the sea, and afterwards became simply an emblem of ideal beauty; while the figure of Adonis was probably designed to represent the more abstracted idea of life or animation. Some of these hieroglyphic designs seem to evince the profound investigations in science of the Egyptian philosophers, and to have outlived all written language; and still constitute the symbols, by which painters and poets give form and animation to abstracted ideas, as to those of strength and beauty in the above instances.

And next, some interesting extra connections. In addition to being an astronomer, Herschel was also a composer, though he’s now more known for his astronomical contributions than his musical ones, but nevertheless there’s another connection with composer Haydn. And as for Haydn and Ann Home, the libretto she wrote for The Creation was not the original but an alternative text meant to replace an earlier clumsy one that had apparently been translated from English to German and back to English (so imagine the Google-like translation errors!), but this was not the first musical collaboration between the two. Haydn had earlier set a number of Home’s poems to music, so I suppose she was returning the favour. Home’s husband John Hunter and his friend Edward Jenner also have a small footnote in the story of evolutionary science, I suppose, not that they would have known it at the time. Jenner was the first person to describe the special adaptation the cuckoo chicks use in the process of brood parasitism (which you can hear more about in my video “Cuckold”). It had been believed that the adult cuckoo depositing its eggs in another bird’s nest knocked the other eggs out, but as Jenner described to Hunter in a letter published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society:

The singularity of [the cuckoo chick’s] shape is well adapted to these purposes; for, different from other newly hatched birds, its back from the scapula downwards is very broad, with a considerable depression in the middle. This depression seems formed by nature for the design of giving a more secure lodgement to the egg of the Hedge-sparrow, or its young one, when the young Cuckoo is employed in removing either of them from the nest. When it is about twelve days old, this cavity is quite filled up, and then the back assumes the shape of nestling birds in general.

And for yet another connection to a previous video, Darwin’s friend Boulton had once employed Rudolf Erich Raspe, writer of the Baron Munchausen stories, which I mentioned in the “Freebooting”.

And finally we return to the topic of science communication. In a 2013 episode of The Infinite Monkey Cage, co-hosted by Brian Cox, the panel, including James Burke, discuss the state of science communication. In the discussion they don’t mention YouTube at all as a platform for science communication, but Burke predicts a renaissance of science communication online, and in the years since then this prediction has been borne out with the popularity of such YouTube channels as SciShow, MinutePhysics, Veritasium, SmarterEveryDay, and Periodic Videos. In many ways, modern media like YouTube or Baba Brinkman’s “peer-reviewed” Rap Guides to science topics have indeed led to a science communication renaissance in which imagination has well and truly been enlisted under the banner of science, and a “renaissance” man like Erasmus Darwin would surely have approved.

Update: It seems the multi-breasted Artemis/Diana figure might have become a general Nature symbol in the Renaissance. That would make sense for frontispieces for On the Nature of Things and The Temple of Nature. So maybe they don't represent Diana or Venus, but some generalized Nature figure? Or maybe there are elements of both Diana and Venus subsumed into this figure? Again, any additional information anyone has would be greatly appreciated.