This week we have a double bill of Anglo-Saxon videos! First, on my channel there's a video about the foundations of the English language, as I look at "What’s the Earliest English word?" Then over on Jabzy’s channel, a collaboration between us on the "Anglo-Saxon Invasion".

One of the challenges of putting together a coherent narrative of the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in Britain is balancing the literary historical sources and the archaeological evidence. In broad outline these sources of information are in agreement but there are some inconsistencies. One of the things we just couldn’t include in the narrative of the Anglo-Saxon settlement was a historiographical account of the literary sources, and so I’ll outline a very basic explanation of the sources here. One of our earliest written sources that discusses the Germanic peoples is the Roman writer Tacitus in his book Germania, written around the year 98. Since his approach is ethnographic we might be tempted to take his evidence at face value. However, it should be remembered that Tacitus may have an ulterior motive in his text, criticizing the corruption he saw in his own Roman society and thus making out the Germans to be a sort of “noble savage” people. Also, we don’t really know where Tacitus got his information from. That being said, he does seem to mention the Angles, as well as the Frisians (along with many other Germanic tribes).

Our earliest detailed account of the Anglo-Saxon arrival in Britain is Gildas's The Ruin of Britain. Gildas was a Celtic monk writing perhaps some 100 years after the invasion, and it should be remembered that his text is not a history, but a religious polemic that paints the coming of the Saxons as a divine retribution for the sins of the Britons, so again, he too has an ulterior motive. Gildas refers exclusively to the Saxons, which seems to have been a generic term for the various north Germanic peoples. In fact Saxon appears to be not an ethnic distinction, but a confederacy of various Germanic tribes. The name Saxon, by the way, seems to come from their favourite weapon, the seax, a kind of sword or dagger, a word which appears to be related to the word section, from the idea of cutting or dividing. So with the Angles being named after their fishhook-shaped homeland, the Anglo-Saxons are literally the fishhooks and swords!

Bede, an Anglo-Saxon writing nearly 200 years later, bases his account of the invasion in The Ecclesiastical History of the English People heavily on Gildas, though he may well have had other sources as well. Bede was a careful historian, who was clearly striving for accuracy, and he does his best with the limited information he had to establish a consistent chronology of events as he knew them. Of course Bede was specifically concerned with ecclesiastical history, that is the history of the church in England, so this can also be seen to colour his depiction of the events. He specifically names three groups of people arriving, the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, and tells us where they they made their new homes, the Jutes in Kent and the Isle of Wight, the Saxons in Essex, Sussex, and Wessex (literally the East Saxons, South Saxons, and West Saxons), and the Angles in East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. The West Saxons are also at times referred to as the Gewisse. Bede also reports that the ancestral area of the Angles remained empty after they left, and there does seem to be archaeological evidence of this area being deserted ca. 450 due to rising sea levels. As for the Jutes, the obvious place of origin for them would be the Jutland peninsula, north of the Angles, but it’s assumed that the languages spoken in that region were probably north Germanic, more closely related to Old Norse, rather than the Anglo-Saxon dialects. This is a bit of a linguistic puzzle. One suggestion is that the Jutes who came to Kent stopped over for a time with the Franks, and so represented something of a hybrid group. This would make sense as the archaeological finds in Kent are kind of Frankish in nature. There’s also been some attempts to connect the Jutes with the Geats, Beowulf’s people in great Old English epic poem Beowulf.

There are also some minor sources from early on of the Anglo-Saxon arrival. Procopius, a Byzantine historian writing around the same time as Gildas in the 6th century, reports that Britain was comprised of three races, the Angles, Frisians, and Britons. This would make good linguistic sense, as Frisian is linguistically the closest Germanic dialect to Old English. Another minor source, the Gallic Chronicle, for the year 441 mentions Saxon invaders. The reality is likely that it was multi-ethnic groups that settled in Britain, and that the divisions weren’t as clear-cut as Bede makes them out to be, but in any case the archaeological evidence does more or less support this picture.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles are a rather late source, dating from around the time of King Alfred the Great (in fact probably a royally appointed endeavour, and you can imagine how foundation stories would be useful to a king with country-unifying ambitions), but possibly drawing on sources of information now lost. The Chronicles provide a rather detailed account of the progress of the various Germanic invaders as they penetrated more and more of the Celtic Britons’ lands. Most of the detailed info in the video is drawn from this source. In addition to the West Saxon foundation story of Cerdic and Cynric mentioned in the video, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles also mentions two other West Saxon foundation stories, Port and his two sons Bieda and Mægla arriving in Portsmouth in 501, and more West Saxons including Stuf and Wihtgar arriving in 514. Many of these accounts may be rationalizations attempting to explain placenames, such as Port in Portsmouth. And indeed Cerdic’s name is suspiciously Celtic sounding. Certainly the precision of the annalistic dates given in the Chronicles is suspect. Nevertheless the Chronicles are our best evidence for the progress of the Anglo-Saxon invasion.

And that brings me to an issue I’ve been dancing around until now. Are we talking about an invasion of a small number of elite warriors or a large-scale migration? This is a hotly debated question, and one I don’t intend to try to answer here. Archaeological evidence suggest a slow process, one way or the other, with more Saxon burials found in the south and the midlands, and Anglo-Saxon rule north of the Themes only in the 6th century (which is consistent with the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles). The increasing number of grave sites over time suggests continued immigration throughout the 5th and 6th centuries. We also have placename evidence such as placenames ending in -ingas, like Hastings, commemorating followers of someone named Hæsta. And we can work backwards from the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the subsequent great census known as the Doomsday Book compiled in 1086, which suggests that by then England contained less than half its late Roman population. That would suggest substantial depopulation during the Anglo-Saxon period. Most recently we have genetic evidence. There have been multiple genetic studies of the current population of England to determine the degree of Germanic settlement. The results of these studies are contentious and uncertain, but perhaps suggest only a small Germanic impact on the genetic heritage of England.

One of the most famous events of the Anglo-Saxon invasion is the Battle of Mount Badon. Gildas tells us that the Britons were led by Ambrosius Aurelianus, whom Gildas identifies as the last of the Romans in Britain whose parents had “worn the purple” (however you wish to take that). Some have identified Ambrosius Aurelianus as the inspiration for the figure of King Arthur, or made connections between him and another proto-Arthur figure Riothamus, said to have been king of Britons in Gaul. But we don’t really know when or where this battle was fought. Gildas dates it to the year of his birth, 44 years before he wrote his account. Bede dates it to ca. 493 and the Annales Cambriae to 517. A later Welsh writer Nennius, writing in the 9th century, explicitly connects Arthur to the Battle of Mount Badon; his account of these events is very much tinged with romance. And speaking of the Welsh, by the way, it should be pointed out that the word Welsh is itself an English word, from Old English wealh meaning “foreigner”. In Welsh, Wales is called Cymru. So the takeaway from this whole story, I suppose, is that the Britons were eventually made to be foreigners in their own country.

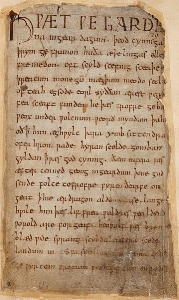

A few final words about Old English, the language of the Anglo-Saxons. As I said in the “What’s the Earliest English Word” video, our manuscript evidence for Old English is all relatively late, from the 9th to the 11th century, but we have various artifacts with earlier Old English inscriptions. One such artifact I didn’t mention is the Ruthwell Cross, a large stone cross located in Ruthwell in what is now Scotland. It has inscribed on it in runes a part of a poem of which we have a later manuscript copy known as the Dream of the Rood. It dates from around the same time as the Franks Casket, the early 8th century, though I’m assuming possibly a little later, from what I can tell. I won’t really get into the dating of the poem Beowulf, possibly ranging from the early 8th century to as late as the 11th century, contentious an issue as it is. Of course some have argued that it existed in some oral form earlier than the 8th century, but that’s a discussion for another time.

And one last sideline. We saw in the earliest word video a running theme of the foundations of Anglo-Saxon England, as well as an interesting parallel with the foundation story of Rome with Romulus and Remus being suckled by the she-wolf, pictured on both the Franks Casket and the Undley Bracteate. Well if you’re therefore wondering what the earliest Latin word is, we seem to have the answer in an inscription on a Roman artifact called the Praeneste fibula. The inscription reads: “MANIOS MED FHEFHAKED NVMASIOI” meaning “Manius made me for Numerius”. A fibula, by the way, is a safetypin-like brooch for fastening garments. The word fibula is now also used to refer to one of the bones in the lower part of the leg running from the knee to the ankle, and forming part of the ankle joint, because of its resemblance to the brooch. But this might remind us of the astragalus ankle bone that has raihan “roe deer” inscribed on it, one of the candidates for the earliest English word.