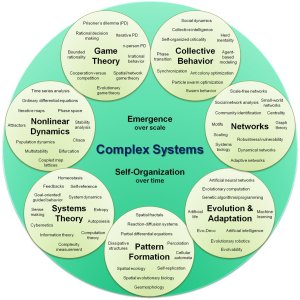

This is the last of the background posts I had planned (for the time being anyway). In the others, I have written about cognitive philology, interdisciplinarity, and interconnectivity. Here I wish to briefly state my position on linguistic relativity. I’ve touched on the topic before in a number of other posts, and it was the focus of a conference paper I mentioned, but I thought it was worth briefly summarising in one post what exactly linguistic relativity means (to me in any case), and what position I take on this often controversial topic. I’ll break it into two posts to keep it from being too long, so expect the second part to follow shortly. I’ve briefly explained linguistic relativity before, but here in more detail is the summary I originally wrote (in slightly modified form) for a conference paper, with special focus on some recent research on the topic by Lera Boroditsky.

The idea of a relationship between language and thought was touched on to some extent by such early 20th century anthropologists as Franz Boas and Edward Sapir, but is was really due to the systematic treatment by Benjamin Lee Whorf, a student of Sapir, that it became a focus of attention. Though Sapir himself never directly argued for a strong causal link between language and thought, Whorf’s bold claims about such a connection have led to the idea being often referred to as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Simply put, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis proposes that differences in linguistic features (and that could be anything from words to the kinds of grammatical information expressed in a language, like verb tense, to syntactical structures used) from one language to the next determine or at least influence the ways in which speakers of those languages think about the world. For instance, Whorf made the observation (largely incorrectly as it turns out) that “the Hopi language is seen to contain no words, grammatical forms, constructions or expressions that refer directly to what we call ‘time,’ or to past, present, or future” (57) and thus he concluded that it was “gratuitous to assume that Hopi thinking contains any such notion as the supposed intuitively felt flowing of ‘time’” (58).1 There have come to be two versions of this hypothesis, the strong and weak versions, sometimes distinguished as linguistic determinism and linguistic relativity. The strong determinism version maintains that the particular linguistic categories available to a speaker determine and constrain what the speaker is able to think, whereas the weak relativity version states only that language differences can lead to differences in thought. While few scholars still hold to the strong formulation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the weak version has remained an open question.

For much of the latter half of the 20th century, this notion fell out of favour and has been strongly rejected, especially after Noam Chomsky first proposed the notion of a universal grammar, which has since become the mainstream position. Chomsky specifically rejected Whorf’s idea of linguistic determinism, and instead held that language differences were surface-level only, and that all humans shared a common grammar driven by a common faculty of language acquisition. More recently, Steven Pinker states unequivocally that the theory is “wrong, all wrong”, and instead argues for an underlying language common to all people, which he calls ‘mentalese’, and further proposes that humans possess an innate instinct for language which has evolved through natural selection.2 Indeed the mainstream view for the past half century has been to search for universals in human language, and to assume that human cognition too is universal regardless of linguistic differences. As Whorf’s linguistic observations had fallen through, and in the absence of much real evidence in support of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the notion of linguistic relativity remained either a fringe view or one of mistaken popular conception only.

However, in more recent years, perhaps only the past decade or a little more, many of these mainstream notions in linguistics have been challenged. For one thing, linguists are more and more starting to challenge the idea of a universal grammar,3 especially in the light of cognitive linguistics which seeks to explain linguistic phenomena on the basis of general cognitive principles rather than specialised language mechanisms. Furthermore, new experimental evidence in support of linguistic relativity is being generated by a number of cognitive scientists, most notably Lera Boroditsky, along with her various collaborators and other researchers working along similar lines.

Boroditsky’s research is based mainly on experimental procedures, often involving cross-linguistic evidence, generated by conducting controlled lab experiments on native speakers and measured by very quantitative results such as response times. She has conducted research on such phenomena as colour perception, demonstrating that possessing particular colour categories in one’s language improves one’s performance in non-linguistic colour discrimination tasks. Thus Russian speakers can more quickly distinguish between two distinct and mutually exclusive shades of blue, goluboy ‘light blue’ and siniy ‘dark blue’, than English speakers, who collapse all such shades under the one umbrella term blue. Boroditsky has also shown the effect of agentive language on eye-witness memory, with speakers of languages that grammatically require an agent even for accidental events having better memory of the agent involved in an action which they have witnessed; this is the case with English, which uses more agentive language, as opposed to Japanese or Spanish, which use less agentive language, for instance. The quantity of agentive language also correlates with the assignment of blame and even harshness of penalties, both in laboratory experimentation and in analysis of court transcripts. Boroditsky has also demonstrated that grammatical gender has an impact on how we think about objects, assigning gendered qualities to them and influencing how abstract concepts are allegorised in art, a result that will be of little surprise to most art historians.

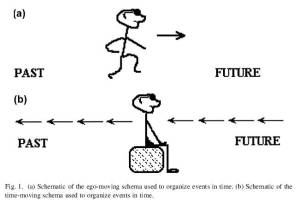

Boroditsky has also done a considerable amount of work on time cognition, particularly the use of spatial metaphor for describing and reasoning about time. She has demonstrated, for instance, that different languages use different spatial metaphors, front/back in English, and up/down in Mandarin. It turns out that people use these varying spatial-temporal metaphors even in non-linguistic cognitive tasks, and thus think about time in different ways. Also in terms of spatiotemporal metaphor, one can think of either time moving, as if you are watching a river flow towards you, for instance, as in “the holidays are approaching”, or ego-moving, as if you yourself are moving along a path “we’re rapidly coming to the end of term”. And it turns out you draw on spatial reasoning actively, and being primed with one spatial arrangement or another can affect your performance of temporal reasoning. Furthermore, whether you conceive of time as moving left to right, as English speakers do, or right to left, as Hebrew speakers do, seems to be dependent on the writing direction in your language; as well, different languages conceive of the future either in the front, as in English, or behind, as in Aymara. And in reversing the perspective, ego-moving or time moving, we also reverse the directionality, such as front/back. Thus, in ambiguous statements such as “We moved the meeting forward a day”, forward can be taken to mean more in the future or less in the future. Perhaps most striking are the differences between languages which use body-relative indications of space, as in right and left in English, and languages which use only absolute directions such as cardinal directions (north, south, east, west). The Pormpuraaw languages of Australia, such as Kuuk Thaayorre, are such languages. Speakers of these languages are always aware of their absolute spatial orientation, and furthermore draw on this spatial reasoning for reasoning about time, always arranging pictures in temporal order east to west regardless of the orientation of their own body. Differences in metaphors used for duration of time are also cognitively significant, such as with linear distance in English as in “a long time” and amount in Greek “poli ora” or “much time”.

With many of these effects, Boroditsky has demonstrated that not only does the brain seem to use language online for non-linguistic tasks, which can be demonstrated by running language interference tasks which disable one’s ability to use language in the moment, but also that the effects of language differences are also long-term. Thus bilingual speakers perform differently depending on the linguistic context – they essentially think differently depending on which language they are using. But also, learning a new language can change your cognitive performance even when you are currently using your old language, and can even change how you speak your own language, and thus speakers of languages in which tense-marking is optional have been shown to mark for tense more often if they speak another language which requires tense marking. Of course Lera Boroditsky is not the only scholar working on the question of linguistic relativity, but I mention her work in detail since much of it focusses on language and temporal reasoning, which is of particular interest to me.4

In the next post I’ll touch on some of the more recent reactions to this research and talk a bit about my own take on it.

1 Benjamin Lee Whorf, Language, Thought & Reality (MIT Press, 1956). [back]

2 Pinker's book The Language Instinct was so persuasive to me, in spite of the fact that I now think he is in many ways fundamentally wrong on this, that I think I was rather too timid in the position I took in my doctoral dissertation. [back]

3 A very broad debate that I can’t go into here but see this article for a thorough treatment of the topic. [back]

4 There is of course much I’ve left out here, such as the “thinking for speaking” model of Dan Slobin, but I wanted to focus mainly on the aspects that are most relevant to my own interests. If you want more information on this topic, you would also be well advised to read Boroditsky’s entry on linguistic relativity in the Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, as well as this more detailed and somewhat more critical account from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. In future posts I’ll also go into a bit more detail about Boroditsky’s work on time which I’ve summarised above. [back]